Last updated on January 25, 2024

At least for people speaking colloquial Indonesian, mau (normally pronounced mo) can be used both to express a desire (“want”) and also to express an intention (“will”). What is happening here? Can words just arbitrarily change their meaning?

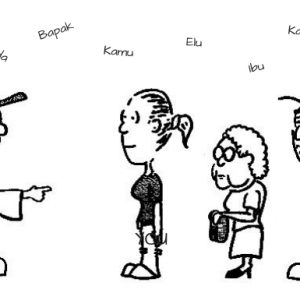

I first learned that the Indonesian word mau means ‘want’. So I was quite confused when I was obviously heading home, and a friend asked me Mau ke mana? Literally, this would translate as “Where do you want to go?”, but it turns out that is not always a question asking about desire. It also can mean “Where are you going?” It is often used when saying goodbye to friends, and in this case, it is a question about intention.

Etymology

The study of how a word changes its meaning over time is called etymology. It is considered part of the field of historical linguistics. Historical linguists study the many ways that languages change over time, and in doing so, some common patterns have emerged.

The change that is happening in the word mau in Indonesian turns out to be a very common one. This connection between desire and intention shows up in the history of languages all over the world—including in English.

The English Word “Will”

Think about the English word will. In modern-day English, this word is primarily used to express future tense. However, in the past this word was used to express desire. The older meaning of the word is still preserved in a few places in modern English, for example, in legal documents (last will and testament) and in theological jargon (God’s will).

When English speakers stopped using will to express their desires, that role was picked up by the word want. Interestingly, the word want also underwent a semantic shift. It used to express a need. That is why old translations of Psalm 23 famously say I shall not want to mean “I won’t be in need of anything.”

Only time will tell if Indonesian will continue to change so that mau will no longer be used to express desire. If it does, will this change only happen for speakers of Jakartan Indonesian? Or will other varieties of Indonesian follow suit?

Further resources:

Beginner:

YouTube video series from The Ling Space on topics in Historical Linguistics.

Intermediate:

YouTube video series from NativLang on etymology and historical linguistics.

Advanced:

Campbell, L. 2013. Historical linguistics: An introduction. Edinburgh University Press/MIT Press.

Heine, B., Kuteva, T., 2002. World lexicon of grammaticalization. Cambridge University Press.

Who says that the meaning of mau is changing?

- Ewing, M.C., 2018. Investigating Indonesian conversation; Approach and rationale. Wacana 19, p. 342-374.

- Sneddon, J., 2006. Colloquial Jakartan Indonesian. Pacific Linguistics. p. 45, 123

About the author: As a linguist, Joseph Lovestrand is mostly interested in studying indigenous languages, and seeing what they have to tell us about how we communicate, think and live. His research began in Africa. He lived for a year in Chad, studying the Barayin language in order to help them establish their first ever literacy program. He also spent four years working in Cameroon where he managed projects supporting indigenous language communities and did field research on the Nyokon language. His most recent linguistic work has been in Indonesia, where he has consulted on a literacy program for the Kodi language in Sumba. Read more at: www.josephlovestrand.com